St. Patrick of Ireland

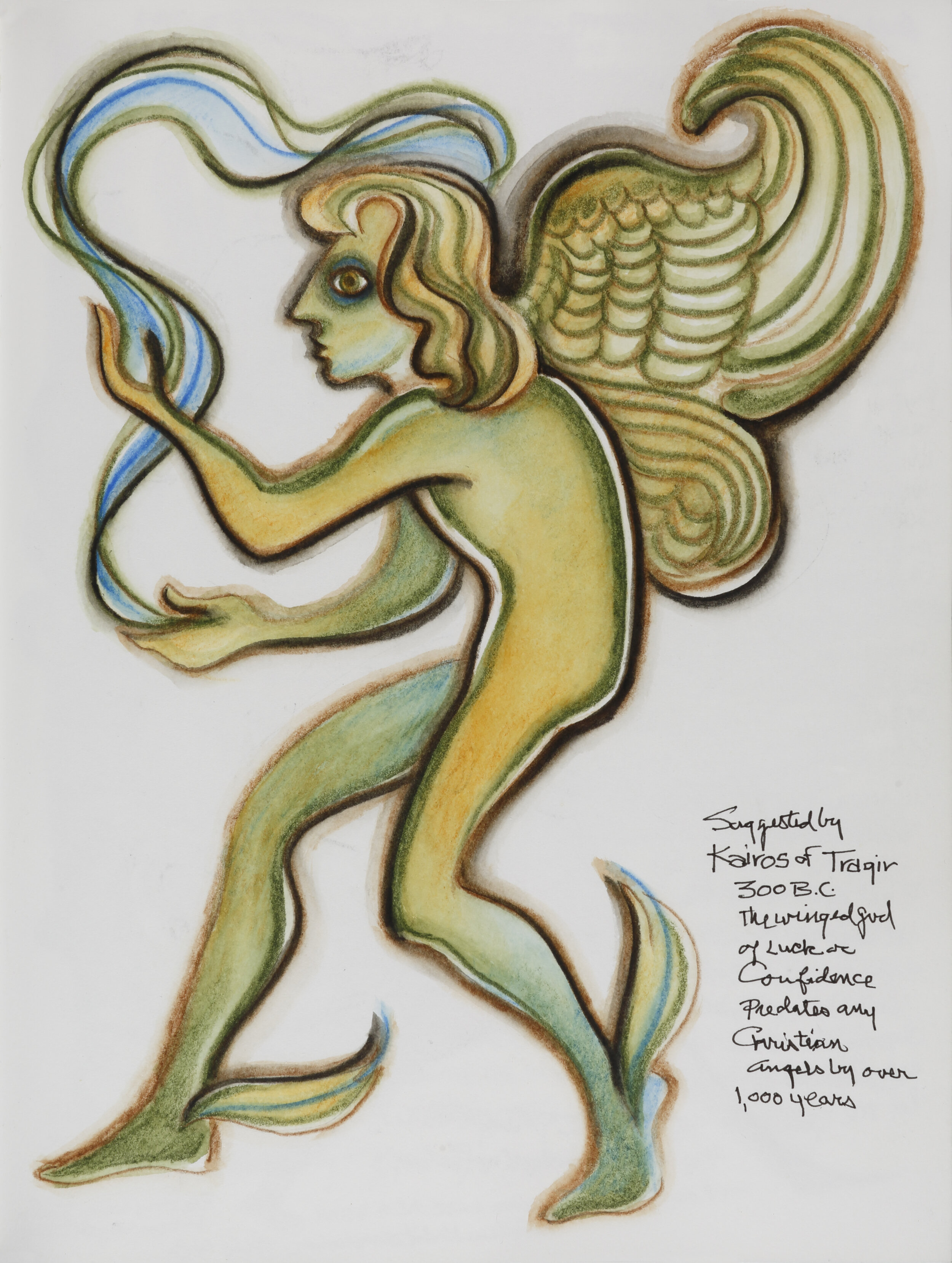

This image is from the artist Jon Arfstrom’s diary #46. The page text reads, “Suggested by Kairos of Tragir 300 BC. The winged god of Luck or Confidence predates any Christian angels by over 1,000 years.” (Object ID 2016.1690.46

The Anoka County Historical Society collection contains post cards like these celebrating holidays such as St. Patrick’s Day.

St. Patrick’s Day is typically commemorated with parades, green beer and donning green attire. The jovial holiday finds its roots in both true stories and some interesting tales about St. Patrick, the patron saint of Ireland.

Patrick not only significantly advanced Christianity in Ireland, but he was also an advocate for the Irish Christians. There are two known surviving written works of his. One is the Confessio, his spiritual biography, and the Letter to Coroticus, which condemns Britain’s treatment of Irish Christians.

Patrick’s legacy inspired some unique legends about him including how he cast all snakes out of Ireland and how he used the shamrock to explain the Holy Trinity (three persons in one God). Once all these stories and legends are stripped away, people discover that not only did Patrick not have any interest in Christianity in his early life, but that he was not even Irish.

Likely born during the Roman emperor Theodosius’ reign (347-395), Patrick lived in Roman-controlled Britain, near the town of Bannaventa Berniae. Patrick came from an aristocratic and wealthy family. Patrick’s Latin name even denotes his higher class; Patricius means “noble, of the patrician class.”

When Patrick was 16, the Celts raided the town, captured the young Patrick and carried him off to Ireland. For six years, the enslaved Patrick worked as a shepherd, a sharp contrast to the high-society lifestyle he had been living in.

It was during this time that Patrick learned how to be a leader as he guided and cared for his flock. He also rediscovered his faith through his ordeal.

“(I was) like a stone deep in a mud puddle, but then God came along and with his power and compassion reached down and pulled (me) out,” Patrick wrote. “God used the time to shape and mold me into something better. He made me into what I am now–-someone very different from what I once was, someone who can care about others and work to help them. Before I was a slave, I didn’t even care about myself.”

After two nights of hearing a voice speak to him in a dream, Patrick planned his escape, returned to Britain and reunited with his family. This homecoming did not last long. Soon, Patrick had another dream, one where he received a letter from “The Voice of the Irish” who called upon him to “come here and walk among us!”

Philip Freeman, author of “St. Patrick of Ireland,” notes that Patrick was likely not the first missionary to Ireland. He notes that local churches of the Middle Ages in southern Ireland stated that their founders came before Patrick. Freeman speculates that the Druids initially thought Patrick was insane and rejected his teachings. Yet, when Patrick’s ministry reached the children of kings, he could no longer be ignored. Patrick’s ministry would likely cause many Druids to feel that their established religion was threatened.

Freeman notes that the resistance Patrick faced from the Druids was from native priests who desired an end to the new religion quickly making an impact. Based on other historical accounts, the Druids would not have given up their religion without a fight.

Through Patrick’s ministry, lower-class and even higher-class citizens accepted the faith. According to Freeman, society outsiders such as women and slaves, were particularly interested in Christianity during the Roman Empire. Even after Patrick died, his mission continued, and the first High King of Ireland became a Christian.

Clare Bender is an Anoka County Historical Society volunteer.