Railroads in Anoka County: 1857 – 1995

Train depot in the City of Anoka (Object ID 2018.1791.002)

By Chuck Zielin

The 19th century American industrial revolution dynamically changed our society. We moved from an agrarian way of life to an agrarian/manufacturing combination. British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli captured this upheaval when he said, “In a progressive country change is constant, change is inevitable.” This article is about one of the catalysts that contributed and stimulated revolutionary changes in Anoka County in the 19th century.

Not many readers are aware American railroading began in the first quarter of the 19th century along the eastern coastal plain. Westward development was blocked by the Appalachian mountains. In the late 1820’s a group of Baltimore financiers pooled their resources and formed the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad to challenge the labor intense, slow-moving and expensive canal system. By 1828 B & O construction had breached the mountains thus opening westward movement on a massive scale.

The Northern Pacific Railroad had a depot on the north side of the railroad tracks. Any rail cars that were destined to the north side of the tracks had to be switched by the N.P. Likewise any cars that were destined to the south side of the tracks had to be switched by the Great Northern RR. The depot was located just off 7th Avenue and on the north side of the tracks. I believe it was 1947, that the depot was removed from the siding. (Information from page 53 of the book City of Anoka, Then & Now, compiled by Charlie Sell (Object ID PCS049)

Bridges have played a major role in the economic development of Anoka County. Completion of the rail trestle in 1867 was an important addition to this legacy. Spurs were then built connecting local manufacturing sites with state and national markets. By 1892 Anoka had a sophisticated infrastructure along its expanding spur. Combined with Mississippi River traffic and the military road traffic, the City of Anoka, as well as the growing county, became a major economic hub.

Railroad development during these years was a very speculative business. The original Minnesota & Pacific Railroad could not find sufficient funding to complete its charter and dissolved. The new company, the St. Paul & Pacific, also fell on hard times in 1879 and was reorganized by James J. Hill as part of his newly formed St. Paul, Minneapolis & Manitoba Railroad. Using ownership of the SM&M and management control of the soon to be Northern Pacific, Hill leased (1883) half of the SM&M’s right-of-way (St. Paul to Sauk Rapids) to the NP. This connected Hill’s northern line directly to St. Paul and eastward. Construction was completed in 1884 forming two separate lines owned by two separate railroads running on the same right-of-way as they traversed Anoka County.

Hill further consolidated his holdings to form the Great Northern in 1889 and then went on to gain full control of the Northern Pacific by the late 1890s. His ability to take over and combine economically distressed railroads greatly influenced Anoka County by what the Great Northern and later the Northern Pacific could offer: Easier access to markets; cheaper shipping costs, and an interconnected system of common gauge track running on a standard time schedule.

In 1905 they (GN & GP) built two Rum River bridges, upgrading them to a steel deck plate and girder structure with stone and masonry piers and abutments in order to carry larger and heavier loads. Today, when you are going over the Pleasant Street bridge, you can see these structures. Although rebuilt in 1926 and 1970, with the exception of the center pier with its steel pilings, they retain their original appearance.

As a result of trains going both ways on a single track, increased usage and volume, and a not very sophisticated communication system, the arrangement became intolerably inefficient for both companies. More than once, the two lines were denied the right to consolidate by the Interstate Commerce Commission over monopoly concerns. To overcome these problems, they formed a contract (1906) to share the lines and costs. The Northern Pacific tracks, being on the north, would be the westbound track while the Great Northern southern track would be the eastbound track – two-way directional traffic just like our highways.

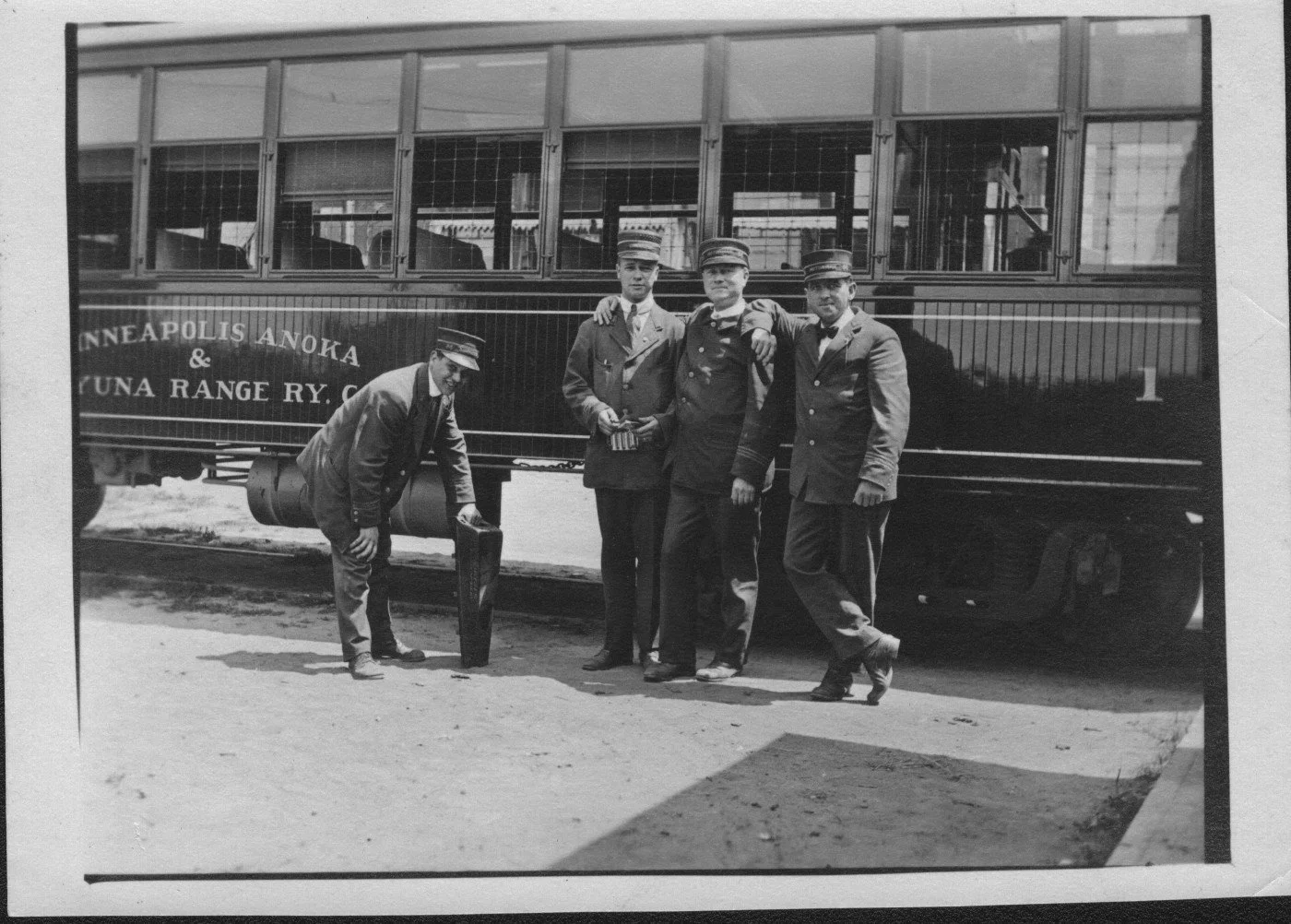

Photo of four operators standing along side the Depot for the Minneapolis Anoka Cuyuna Range Ry. Co. The Depot was located on the west side of lst Ave approximately where the parking lot for the present City Hall is located. Date of the photo circa 1917. (Object ID 909.3.00)

Photo of the Anoka depot with the Pillsbury Mill in the background (Object ID SC452)

End view of the Bethel depot with train, automobile and people visible (Object ID P2079.3.43)

As the military road and rail line corridors were developing with European settlement, the outlying cheaper land continued to be attractive because of the economic incentives; lower interest rates, cheaper pricing and easy loan acquisition, the positive labor and product markets.

An example of rail construction into a sparsely populated area is the Coon Creek junction cut off. The GN split its line in 1899 going north with planned stations every five miles: Andover (1912); Cedar (1908) Bethel (1899) and Isanti. The cut off facilitated settlement, but it also represented the further development of infrastructure in Anoka County as it opened the Duluth/Superior ports to our manufacturing sector. An earlier example was the building of the Anoka spur just west of the original depot. Built by the GN, it created direct access to the Lincoln Mill, the Washburn Lumber Mill, the Rum River lumber complex, Tim’s Standard Oil, different creameries, Birch Printing, LaPlant coal sheds, cement sheds and potato warehouses. Combined with the parallel spur line of the Minneapolis Northern Line (1912-14) and then the Anoka & Cuyuna Railroad (1915-1946), the line followed Coon Rapids Boulevard and East River Road. Most people remember this line as the “trolley” line. However, the biggest revenue source was freight.

The trolley side of the line was mostly a stop-and- (hopefully) go affair. First attempts (1912-13) at finding a power source to drive the trolleys centered on gasoline engines that consequently failed. Second efforts involved a hybrid approach of steam and electricity. Electricity won by using overhead lines with electricity supplied by the new Coon Rapids Mississippi River Dam (1915). Passenger service thrived into the 1920s, then declined until 1939 when some overhead lines were blown down. High replacement costs and low ridership resulted in the discontinuing of trolley service.

Return to individual transportation in Anoka County came from the rapid expansion of auto and truck usage. As the Anoka community turned to the car in ever increasing numbers, the corollary was the decline of mass transit. In Anoka County MACRR stopped trolley service in 1939 and went out of business in 1946. Passenger service on the GN and NP also declined resulting in its elimination locally plus the abandonment of branch lines.

With the loss of federal subsidies after WWII, rail passenger service became dependent on profits from moving mail and express items. When the US Postal Service took over mail shipping in 1969, it was the final straw; even continental passenger service would be eliminated. Congressional reaction was to create Amtrak, the National Railroad Passenger Corporation, in 1971 for continental service. Locally, we have created our own mass transit interurban system, the North Star Commuter.

After many attempts to combine the GN and NP, the ICC finally agreed to the merge of the two in 1970 creating the Burlington Northern. In 1995 the BN merged with the Sante Fe forming what we see today: The BNSF.

Railroad development in our county began in 1857 under very speculative conditions and involved federal and provincial subsidies to facilitate development. The high cost of construction and maintenance combined with a volatile market caused many bankruptcies, which resulted in James J. Hill taking advantage of the closures to create his empire. In Anoka County it was the connectivity of the GN and later the NP to national markets that promoted growth. Branch connections, spurs, sidings and depot development gave us an infrastructure that facilitated growth. Today we are more a “pass through” site than the once in-depth participant we were. The spurs to local mills and manufacturing units are long gone, as are the mills and factories they served. The last vestiges of the “Golden Age of Railroading” (1864-1928) are rapidly disappearing or are already gone. The Anoka spur steel plate and girder bridge crossing over Highway 10 between 4th Avenue and Ferry Street is a perfect example – it is to be removed when Highway 10 is rebuilt. Other remaining examples are the three bridges over Coon Creek Boulevard and the two bridges across the Rum River.

In Minnesota our territorial legislature entered the railroad movement in 1857 when it chartered the Minnesota & Pacific Railroad. The M & P received private funds and ownership of native lands totaling 2.6 million acres to establish a main line from St. Paul to Breckenridge and a secondary line from St. Paul to the Katab sawmill complex in Sauk Rapids. While the right-of-way was surveyed and cleared only a few miles of track were laid before the charter expired. All rights and inventory were transferred to the newly formed St. Paul & Pacific Railroad. With English financial backing, tracks were laid to St. Anthony in 1862 and Anoka in 1864. Construction of a wooden trestle across the Rum River in 1867 connected the 62 miles of track.

Before the coming of the military road and the railroad, the Anoka area had served as nothing more than a seasonal fording site for the Red River Ox Trail over the Rum River. Construction of the military road, with its bridge across the Rum River, changed everything. In the early and mid-1850s Anoka became an area of land speculation and rapid growth. By 1864 Anoka had a thriving economy in flour, lumber and, of course, potatoes and starch. It was not a coincidence Anoka went all out to celebrate the opening of the rail line from St. Paul to Anoka on January 20, 1864. The “Legislative Excursion” with 250 VIPs “arrived around 1:30 PM at the depot.” They traveled to town in sleighs, were met by “a cannonade, band music and welcoming speeches.” One speaker noted the absence of Native Americans when he said, “fifteen years earlier...there were no homes here...the Sioux owned the west side of the river, the Chippewa this side...how things have changed.” This was followed by a “grand” luncheon at the Lufkin, Eastman and Kimball hotels. In his speech Governor Miller pointed out that Anoka was not the terminus of the line – meaning Anoka would be integrated into the developing system. This comment set the stage for Anoka County to be a benefactor of the branch line but not a major hub for the line.

Black and white photo of the Twin City Milk Producers factory located at 4th and Pleasant Streets in Anoka, MN. Railroad tracks leading to Main Street are visible in front of the factory. No date for photo. Writing on photograph "Creamery Anoka, Minn” (Object ID P1673.8.07)

The railroad depot in Anoka, MN. This photo is from a glass negative, and probably dates to about 1900. Photo shows 3 tracks, with a train pulled up to the depot on the left. Several passengers are gathered on the platform, and two men are standing on the middle track. (Object ID 0000.0000.247)

To promote rail development, the U.S. Congress, the Minnesota legislature, private banks and local governments provided economic incentives. Congress and our legislature offered grants from land taken from the indigenous population to be used for collateral. State and local governments underwrote loans and bonds. To pay investors, the different companies needed income. This was to come from freight fees, passenger fees, and the sale of 2.6 million acres of land. To pull this all together, from the beginning, the railroad companies turned to immigration.

Immigrants would become a resource for businesses in the form of cash payments for travel, consumption of local products, land purchases, working as a labor source and serving as a product and freight supplier. A sophisticated system of promoting immigration was developed and soon the companies opened various departments of immigration and land development. Starting with targeted northern European centers, the immigration departments sent over delegations of agents who promoted Minnesota through pamphlets, lectures, advertisements, and circulars. They assisted individual and group travel by organizing transportation from their homes to a seaport, to the boat, assistance with disembarking and the registration process, then seeing them onto a train and their destination in Minnesota. Agents, some of whom had official Minnesota diplomatic status, would interact with them at every advertising point. Reception centers or “local facilities, poor as they were, for cooking, sleeping and washing were strategically located in underdeveloped areas to encourage settlement” in that area. If an individual or group wanted to preview a section of land, special pricing and financing could be acquired. To form colonies, the immigration departments often encouraged group travel.

Advertising by the St. Paul, Minneapolis & Manitoba Railroad emphasized positive features of Minnesota to draw Scandinavian, German, and U.K. immigrants to Minnesota. It took advantage of the economic hard times facing these countries. Push factors included economic depression, rising taxation, a miserable job market, a privileged landed class and over-population. Opposing data emphasizes that the small landowner and related farm workers were responding to the advertising through the idealism of a better, material well-being. That it was the promise of a higher standard of living that drew immigrants to the land grant opportunities offered by the SM&M Railroad. In official diplomatic reports, the latter thinking dominated, and in this writer’s opinion, the reports were being “politically correct” so as not to embarrass local governments.

Unfortunately, most immigrants lacked resources to cover the total cost of transportation and homesteads. The rail companies responded by developing creative financial arrangements; discounted tickets, extended contracts, lower yearly payments during the first five years, declining interest rates and employment until a down-payment was achieved or the cost of seed for the first planting was achieved, to say nothing about purchase price rebates. A 10-year contract was common as were 40-acre parcels. A residency, land usage and possibly a building requirement were part of the contract to protect against land speculation. In the final analysis, the “secondary” rail line qualified 2.3 million acres out of a possible 2.6 million acres to meet the requirements of the 1857 land grant making the economic plan of fostering immigration a successful one.

National Guard soldiers at the Great Northern Railway Depot, 1951, looking south. A large crowd gathered to see the troops off, as evidenced by the many cars in the image. The train ran a couple hours late because of some problems at Princeton or Milaca, finally pulling out of Anoka at 5 p.m. According to the Anoka Union of January 26, 1951, each member of the guards received a package prepared by the American Legion and American Legion Auxiliary containing cigarettes, candy, and fruit. In his book, City of Anoka, Then & Now, Charlie Sell remembers this as the second time he went to the depot to see the Guards off—the first being when he was in grade school at Washington elementary, in 1941. (Object ID PCSM056)