A History of Our Own

Two decades ago, the Anoka County Historical Society embarked on a mission to illuminate a forgotten and often shunned story. Since their return, the Vietnam Veterans have frequently gone unnoticed, their valor fading into whispers and scorn. Through the magic of storytelling, ACHS breathed life into their legacy by crafting an exhibit, capturing oral histories, and writing a book, which was unveiled in 2005.

Since then, these 106 tales of bravery have echoed through classrooms and podcasts, stirred the hearts of the curious, and emerged as one of the most requested collections at ACHS. Now, the time has come to inscribe the next verse, welcome the voices of their descendants, and witness the ongoing tapestry of their mending spirits.

Due to circumstances beyond our control, the book Echoes of Bravery has been put on hold. We apologize for the inconvenience. When ACHS has completed Operation Relocation, we will resume the project. Meanwhile, please check our website and podcast for new military history content.

“Local history is powerful and important because it can fill in the gaps left by national or state stories. Our mission is not to explain the global impact or tackle politics. We can document personal experiences and create a legacy for the county to claim as an identity within the larger picture, bringing meaning to the statistics.”

From the Preface

By Rebecca Ebnet Desens

In my experience, very few people smile when they hear the word “Vietnam.”

It’s usually a grimace, maybe a sneer. Sometimes, people even clam up and walk away. Whatever the reaction, it’s instant and strong. In the lucky few instances I’ve had where people find the history center a safe space to share, I’ve heard stories of crushed babies, bartered goods, lost friends, unreconciled guilt, mud, bugs, missed opportunities in life, and the ugly truth of why service members have two dog tags.

As the director, I inherited a relationship with Chapter 470 of the Vietnam Veterans Association. It came to me almost on a platter, handled with care and compassion. I was passing on responsibility to a group of people who had never given up on themselves or their fellow servicemembers despite the odds.

I went to my first meeting of the VVA in 2015, following Vickie Wendel down the stairs to the basement of the American Legion in Anoka, smelling the dampness that comes from a lower level with an insufficient dehumidification system. I turned the corner and entered a small room, chairs lined up on either side of a small aisle, each filled with a man sitting in some level of protected stance – arms crossed, head down, turned sideways with his back to the wall, legs tucked under the chair. Some wore leather vests; others caps decorated with flags or emblems, tee-shirts declaring themselves a veteran. Maybe an MIA bracelet, but I didn’t look closely enough to read it. I remember them smiling when they saw Vickie, watching their shoulders relax and their faces light up. Then, just as quickly, their faces closed, and their muscles tensed when they saw me behind her.

I sat down to her right and waited for the commander to call the meeting to order, for the pledge to be recited, and for her to stand and introduce me as the new director who was a friend. Specifically, those words – an endorsement of continuity in the leadership at ACHS as I took over the job, the assurance that I posed no threat as a stranger, that the stories they donated 10 years prior would continue to be safe under my care. Somehow, when I smiled around the room and waved that night, offering coffee and chats when they wanted to stop in, I inadvertently promised to continue the project beyond just keeping the artifacts safely away from dust and light. It took another 10 years, but this book represents that unspoken promise.

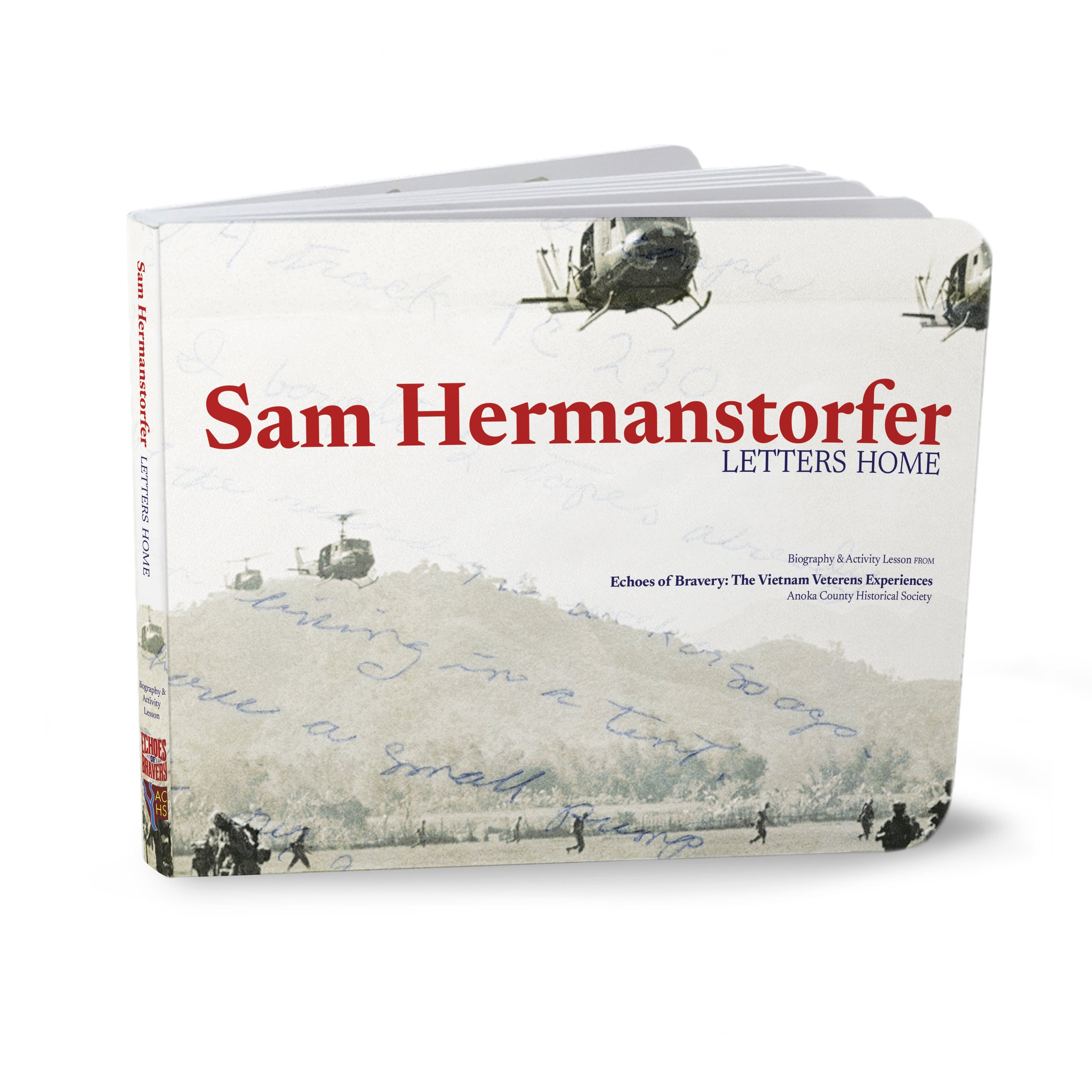

We have spent staff and volunteer time to gather new stories, take a new look at old ones, seek out Vietnam veterans and their families we didn’t know, write grants and discover donors for funding, and above all, hold ourselves accountable to the history on these pages, in our website, and the education totes for the students. We’re too late for some of these veterans to see that silent promise fulfilled – people like Sam Hermanstorfer, who by all accounts was one of the wackiest individuals I have ever met. He died a few years ago, leaving me with memories of his excitement for the Andrews sisters singing on his phone and a mobile made of shells hanging above my desk.

There’s a long list of vets who have either taken their own lives years ago, passed away, moved on, or even lived with the secret of serving, having never told anyone of their experiences. This project comes too late for them, an unfortunate truth about the neverending march of time. But it’s on the mark to commemorate the experience of their families, to share their perspective of living with someone who served.

The children who grew up with veterans as parents lived a unique experience balancing a tightrope between rage and love, timing their interactions perfectly to ensure stability. It’s for the grandchildren who may have had the benefit of a vet healed enough to play and banter but also for those whose Grandpa couldn’t find the ability to engage and stayed stern and aloof. Now, into adulthood, they can see the memories of their youth with different eyes. It’s a chance for the spouses who stayed to explain why and for us to offer compassion for those who left. This project strove to document the reintegration process when Beyond the Yellow Ribbon didn’t exist and when nobody conceived of the Day of the Military Child. The families supported their veterans as best they knew how, whether that was saving artwork the soul created, making space for mowing the lawn in the dark of night or adapting social situations to accommodate moments of PTSD.

The echoes of bravery extend to those on the homefront who wrote letters back to Vietnam devoid of household problems but full of news and dreams of the future. The impact of these echoes can be heard from people like Mary Clark, who said she never feared for her personal safety. Still, there was a period when she feared Mike’s anger would force the authorities to step in and cost the family control of the situation. Documenting the veteran story and the family perspective provides a complete picture of what war costs a community from the microcosm of a family revolving around the emotional and physical needs of a wounded vet to the echoes of that rippling out to extended family, employers, schools, and even the person at the till in the grocery store — how we carry the stress, uncertainty, and compassion needed to survive daily as caregivers affects everything.

Local history is powerful and important because it can fill in the gaps left by national or state stories. Our mission is not to explain the global impact or tackle politics. We can document personal experiences and create a legacy for the county to claim as an identity within the larger picture, bringing meaning to the statistics.

In this case, we create a memory to learn from to avoid repeating history for those who can’t choose their circumstances. The hatred and scorn, the threat of personal danger, and alienation experienced by Vietnam-era families for their service in a war no one wanted in an era when everyone felt the uncertainty of change and violence simply mustn’t happen again. We need a project like this to show how, even 50 years in the future, the echoes of dehumanization have robbed our fellow residents of the carefree life they deserve.

This book is not a compendium of Vietnam history - but we provide enough context and a list of resources at the end to help you make sense of the stories. It’s not a compilation of accounts printed in the newspaper – but those are available at the history center if you would like further context. It’s not an exhaustive list of veterans and their families – but if your experience isn’t represented, we would love to hear from you. It’s not a safe space away from the horror of war, the drama of living with a wounded person, or the profound sadness of a path taken and then left to make the best of it – but it is the truth spoken by residents in Anoka County.

It may be hard to read, so take a break. It may be hard to envision, so close your eyes and try. It may be hard to digest, but that’s okay. For every feeling you have, our veterans have more. For every veteran and their family member reading this – your story matters. It will echo for years to come.

Find out more about the project

by paging through the booklet below

From Chapter 1, “The Draft”

The Vietnam War stands as one of the most contentious periods in American history, not only for the conflict itself but also for how the US supplied its military with soldiers - the laws of conscription, better known as the draft.

The draft was managed by the Selective Service System (SSS), a federal agency responsible for conscripting men between a certain age into our military. As the Vietnam War escalated, the draft became a focal point of societal tension, protests, and calls for reform. These mounting pressures resulted in the introduction of the draft lottery in 1969 and the eventual withdrawal from the war in 1973.

The Selective Service System

The Selective Service System had been in place since World War I, to ensure the U.S. military could call upon a sufficient number of men in need. During the Vietnam War, the system required all men 18 to 26 to register for the draft - for WWII, that ranged from 18 to 46. Registrants were classified by local draft boards, which were community-based and often operated with significant autonomy. These boards decided who was eligible for induction, received deferments, and was exempt from service.

Deferments played a crucial role in determining who would be called to serve - if the local board identified a cause for deferment, a registrant would not have to be called in the draft. Common deferments included education for college students, which allowed many young men to delay service as long as they remained in school. Others received occupational deferments for working in essential industries or medical deferments if deemed physically unfit. The system was criticized for favoring the well-connected and the wealthy, who were often able to secure deferments through education or influence, leaving poorer and minority men more likely to be drafted.

Before 1969, the Selective Service operated under a quota system. Local draft boards were given quotas based on the military’s needs, and within each local jurisdiction, men were called up by age, with older men in the draft-eligible range being drafted first. This approach was a legacy of previous wars, but as the Vietnam War dragged on and the U.S. involvement deepened, the number of men needed increased, leading to more frequent draft calls.

The Introduction of the Draft Lottery

As the war became increasingly unpopular, so too did the draft. By the late 1960s, the draft had become a lightning rod for anti-war sentiment. Protests against the draft were common, and acts of defiance, such as burning draft cards or fleeing to Canada, highlighted the deep divisions within the US.

The Selective Service System, with its perceived inequities and lack of transparency, became a prime target for reform. In response, President Richard Nixon introduced the draft lottery on December 1, 1969. The lottery system was intended to make the draft more fair and equitable by randomizing the order in which men would be called up based on their birth dates. In the first lottery, each day of the year was assigned a number, and those with the lowest numbers were drafted first.

This system replaced the previous method of drafting older men first and ensured that every eligible man, regardless of social status or education, had an equal chance of being drafted. While the lottery system was a significant change and marked a shift towards a more transparent process, it did not eliminate the draft’s unpopularity. Many viewed it as a new way of selecting young men to fight in a war, which was increasingly seen as unjust and unwinnable. Instead of leveling the playing field, the burden of conscription still fell disproportionately on those who could not afford to attend college or secure deferments.